Mediacene

Ecomediatic Sensitivty / Sensibilité éco-médiatique

« We now live in the Mediacene, a geological era characterized by the crucial impact of technologies of perception, information and transport on the historical and environmental context in which we live. Having become real living environments, the contemporary media are regulators of a multi-modal sensitivity on which our awareness of the challenges and pitfalls of the now full-blown ecological crisis depends. This issue offers some food for thought on the current state of the discourse on media ecology, in search of a new eco-systemic paradigm for describing the relationship between living beings and the planet.»

« Nous vivons actuellement dans le Mediacene, une ère géologique caractérisée par l’impact crucial des technologies de la perception, de l’information et des transports sur le contexte historique et environnemental dans lequel nous vivons. Devenus de véritables milieux de vie, les médias contemporains sont les modulateurs d’une sensibilité multimodale dont dépend notre prise de conscience des enjeux et des pièges de la crise écologique désormais manifeste. Ce dossier offre un aperçu de l’état actuel du discours sur l’écologie des médias, à la recherche d’un nouveau paradigme écosystémique pour décrire la relation entre les êtres vivants et la planète. »

Contributors

Franca Franchi, Adriano D’Aloia , Jacopo Rasmi, Giuseppe Previtali, Laura Cesaro, Jan Christian Schulz, Chiara Rubessi, Valeria Burgio, Emiliano Guaraldo, Jérémy Damian, Anna Caterina Dalmasso, Paolo Berti, Vincenzo Di Rosa, Matteo Quinto, Marta Rocchi.

https://elephantandcastle.unibg.it/index.php/eac/issue/view/22

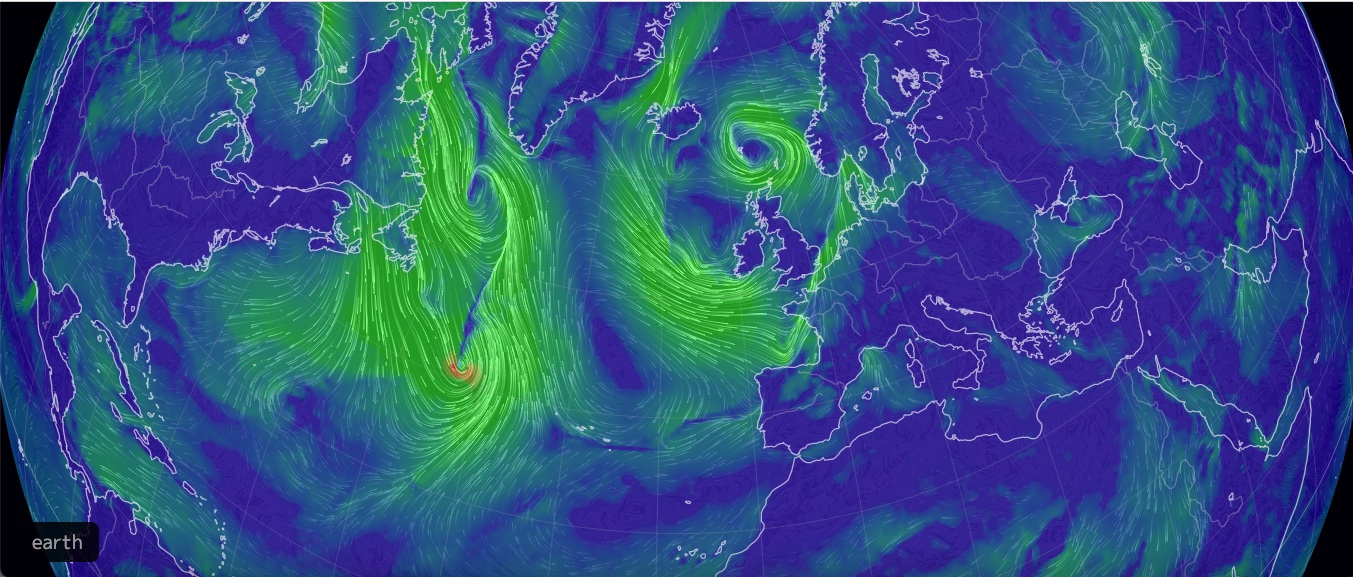

Visualiser des données météorologiques: représentations des phénomènes atmosphériques

Chiara Rubessi

Abstract

Data visualisation technology has made many databases visible and intelligible, and the issue of accessing, analysing, using and visualising data is one of the problems of the digital society. In this perspective, the representation of weather phenomena raises a series of questions about the visualisation modalities adopted. How are the data of meteorological phenomena represented? From this question, the contribution aims to analyze some 2D representations of meteorology through the tool of data visualization in order to observe the way atmospheric phenomena are rooted in the mediation technology.

Meteorology, Visual form, Data visualization, Representation, Phenomenology.